|

RCBJ-Audible (Listen For Free)

|

Village of Haverstraw Museum Forging Partnerships With Universities; Developing 21st Century Programming

By Tina Traster

Nearly 50 years ago, descendants of the Village of Haverstraw’s brick yard families led an effort to keep history alive. The seedlings those founders planted grew to be the Haverstraw Brick Museum, a small cultural and archival nonprofit that educated school children and visitors on an important yet obscure part of Rockland County’s past.

Over time, the museum’s mission veered off course, as it was underfunded and under-marketed. It is difficult to maintain small museums with meager footprints; it is even more challenging to evolve them as times change and people look for a different kind of cultural experience.

“The first question we asked ourselves was ‘What makes it authentic?’” said Whitlow.

Now, with new stewardship in place, the Brick Museum has embarked on a fresh era that includes partnering with colleges and universities such as Pratt, Cornell, and RCC, as well as working with a specialist who has a background in turning around flailing companies. These are important drivers for the cultural gem, which has the potential to be a serious economic engine for the Village of Haverstraw and the Hudson Valley because there is not another regional museum dedicated to the story of brickmaking.

The timing couldn’t be better.

The village is gearing up to choose a development team to transform the fallow waterfront into a mixed-use plan designed to breathe new life into the village. At least one prospective development team is considering integrating a Haverstraw Brick Museum expansion into its hospitality concept for the former Chair Factory site.

Also, the village recently won a $10 million downtown revitalization grant from New York State. The grants are aimed at developing strategic investment plans and implementing key projects that advance the community’s vision.

“The Brick Museum has the potential to be a significant tourist attraction, but we have not yet lived up to that potential,” said Richard Sena, the museum’s president.

In 2019, the museum took a two-year hiatus to complete a $75,000 renovation of the 2,000 square-foot interior at 12 Main Street, to rethink, and to re-brand. The hodgepodge collection needed restoration and laser curating. The efforts relied heavily on Dan DeNoyelles’s written papers narrating his family’s history from 1757 to the 1940s as well as a vast archival collection. Village DPW employees and BOCES students from both Rockland and Westchester counties pitched in with free labor.

The organization updated its bylaws and made the strategic decision to recruit Rachel Whitlow, a company turnaround specialist. Curriculum was rewritten and STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Mathematics) education was defined as the guiding principle for moving forward. Many board members are former educators, using their skills to reshape programming.

The museum built a 21st century website, updated its social media platforms and began offering online adult education webinars.

The pandemic gave the museum the gift of time, a pause to rethink and recalibrate.

“Entrepreneurs often start brands with a lot of vision, but they reach a five-year mark and lose their way,” said Whitlow. “Too often, they don’t have the skill to scale the company. They don’t know how to run the company, so they bring in venture capitalists and the brand loses its way.”

So what does that have to do with a small cultural institution that keeps alive the lore of brickmaking?

Quite a bit. It has been imperative to professionalize the museum, to tie it to waterfront development, to make it tactile and interactive, to grow its treasure to become a formidable cultural gem.

“When you step in to turn around a company, you have to look at what the branding was, what made it special, what was unique about it compared to its competitors, how do you tell the story?” said Whitlow.

The same principles applied to the Brick Museum.

“The brick museum is a narrative,” Whitlow said. “It’s about the history of a community, it’s about a trade craft. At the heart, the most important thing is to capture that narrative voice.” Although the board’s predecessors always had good intentions, it had wandered past its core story, collecting all kinds of period objects, diluting its uniqueness.

The organization turned its energy to paring down and authenticating its new chapter.

“The first question we asked ourselves was ‘What makes it authentic?’” said Whitlow. “We identified our areas of expertise on Haverstraw’s brick industry, on the great Hudson River brick industry, which is part of America’s colonial history. Anything that was not relevant was stored in the basement.”

In the 1800s, Haverstraw was a brickmaking hub; it’s where coal dust was first added to the clay mixture in 1815, which cut burning time in half at the kilns, and where Richard A. Ver Valen invented the first automatic brickmaking machine in 1852. By the middle of the century, Haverstraw was producing millions of bricks a year.

In the 1800s, Haverstraw was a brickmaking hub; it’s where coal dust was first added to the clay mixture in 1815, which cut burning time in half at the kilns, and where Richard A. Ver Valen invented the first automatic brickmaking machine in 1852. By the middle of the century, Haverstraw was producing millions of bricks a year.

By the latter half of the 19th century, thousands of people were employed at the brickyards. But on Jan. 8, 1906, tragedy struck: A landslide caused by the continuous excavation for clay killed at least 19 people and destroyed countless streets, shops, and houses. By the late 1920s, the industry was fading because it was being replaced with cement, cheaper European imports, and even bricks manufactured more cheaply down south.

The museum team is now entering the second phase of its reinvention, partnering with Pratt and Cornell to elevate the museum’s stature.

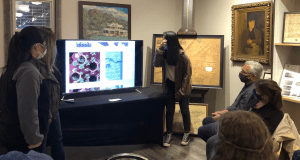

Whitlow said a professor at the Pratt School of Architecture, which was partially built by Haverstraw bricks, contacted the museum to collaborate. The school is working on an innovative 3-D technology for printing bricks. The museum recently held an exhibition of student-made bricks.

Similarly, the museum is collaborating with Cornell’s School of Landscape Architecture, where they are looking at the impact of industry on the environment.

To truly evolve, the museum board says it needs at least a $200,000 annual budget, three employees and weekend staffing. The museum recently received a $6,000 Rockland County Tourism Grant.

“We are establishing a fundraising committee, which is new,” said Sena. “We’re looking for foundations and business partners beyond the grant circle. We’re seeking federal partners that focus on American history, university partners, environmental partners.”

The small museum, ironically, draws tourist from Europe and Scandinavia but fewer from the region.

“Local and domestic tourism for families,” said Sena. “This is what we need to grow.”