Gelling Agent Used In UEP’s Battery R&D Gave Company A Strategic Edge

By Tina Traster

You know those ‘aha’ moments, those jot the thought down on the paper napkin moments because there might just be something there?

That’s exactly what happened at Urban Electric Power, a Rockland-based innovator that has been working for years to develop a small rechargeable, environmentally-friendly battery pack that can power a house through a blackout as well as store usable energy sources.

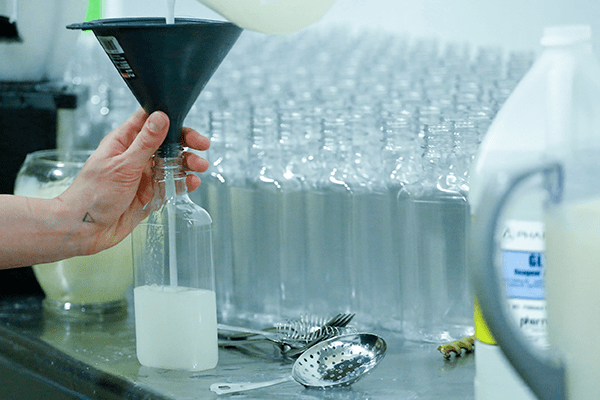

In what no one would have seen coming, UEP over the past few months has thrown resources at manufacturing hand sanitizer, branded Ohm Products. Some pandemic pivots seem obvious. In this case, readers need to understand the smart folks at UEP recognized they had a precious commodity at their fingertips: a gelling agent used in their battery development.

“We were told we had to shut our doors on March 22,” said Gabe Cowles, vp of finance and business development. “We were frantic, but we put our heads together and asked ourselves whether we can make some kind of PPE (personal protective equipment) in order to keep our doors open?”

Sanitizer, Cowles said, was a “natural cross-over” because the company had mixing equipment and hard-to-come-by gelling agents that were in short supply in mid-March and April. Hand-sanitizer ‘want-to-bes’ in the early stages of the pandemic were rolling out “liquidy” hand sanitizers that did not coat the hands and were difficult to refill in dispensers.

Sanitizer, Cowles said, was a “natural cross-over” because the company had mixing equipment and hard-to-come-by gelling agents that were in short supply in mid-March and April. Hand-sanitizer ‘want-to-bes’ in the early stages of the pandemic were rolling out “liquidy” hand sanitizers that did not coat the hands and were difficult to refill in dispensers.

Hand sanitizer formulas are not, rocket science. They are nowhere near as complicated as a clean-tech alternative battery that is cleaner, smaller, and ultimately less expensive.” In fact, formulas – which largely contain alcohol, water, hydrogen peroxide, glycerin, and a gelling agent – are readily available from the World Health Organization.

More difficult to procure were plastic containers, which every small, medium, and large manufacturer was scrambling for as demand soared.

“There was a huge run on containers,” said Cowles. While a small team of UEP chemists were at work mixing batches and testing scents, others were tasked to hunt down plastic. “We spent a huge amount of time looking for reasonably-priced containers to use. At first, we used milk cartons, but we kept searching for containers with pump top dispensers. Ultimately, we leveraged some of our existing relationships with manufacturers that make battery parts because their operations include plastics. We asked them if they can make containers. Within four weeks, we were on our way.”

Americans have been gobbling up hand sanitizer and wipes during the pandemic. Sales volume for hand sanitizer and hand wipes was $200 million and $33 million, respectively, from March to July of this year, according to market research company The NPD Group’s retail tracking service. That’s an increase of 465% and 41%, compared to the same months last year.

The explosion in demand led to the US Food and Drug Administration to temporarily ease restrictions on manufacturers looking to make sanitizer, outlining that “the agency does not intend to take action against manufacturing firms that prepare alcohol-based hand sanitizers for consumer use.” However, that hasn’t quite gone according to plan: more recently, the FDA has warned against using more than 100 hand sanitizer products because their ingredients contain methanol or have insufficient levels of alcohol.

UEP, a startup entity that has been funded by federal and state monies, as well as private investment, has spent more than $25 million innovating clean-tech energy solutions as the national dialogue turns to the perils of climate change, and the forward-thinking initiatives proposed in the New Green Deal. The pioneering technology for UEP’s Power Assurance System began with a research team a decade ago at City College of New York’s Energy Institute. The team discovered that by changing crystal structures, it could make non-toxic alkaline batteries, like those in remote controls, rechargeable for hundreds of uses.

The company, which is not yet profitable, relies on grants and investors. Prior to the pandemic, UEP was moving along steadily toward its goals, developing pilot projects in the US and India. But COVID-19 has thrown nearly every business a curve – leaving uncertain how willing investors will be to spend while the economy reels.

“Our grants won’t disappear overnight but there’s a lot of uncertainty in the cards,” said Cowles. “We are in the process of a fund-raise. Investors may take a more cautious approach, a wait-and-see attitude.”

UEP is largely focusing on selling locally to Rockland County. The Ohm Product line has been generating revenue through sales to school districts, public works departments, and small businesses. Keeping its product competitively priced with national brands, coupled with truck delivery that saves procurement departments shipping costs, has jump-started the sanitizer business. A pack of two 12-ounce bottles costs $24 at retail but the company offers bulk pricing and free delivery in the county. However, Cowles said the e-tail website has begun attracting business from as far away as Kansas and Hawaii.

In April, UEP worked to keep up with the panicked rush for product. Over the past several months, hysteria tapered off and demand has been less acute but steady. UEP has no plans to compete on a national scale with major brands that pump out hand sanitizer but for now the company will focus on building brand loyalty locally.

“We are approaching this with an open mind,” said Cowles. “Companies have to be willing to consider alternatives if they want to stay afloat. We’re not ruling out anything.”