|

RCBJ-Audible (Listen For Free)

|

Haugland Group, Which Bought Plant Property For $2.85 Million, Would Benefit From Passage Of Floating Zone Amendment To Stony Point Zoning Code

By Tina Traster

William (Billy) Haugland Jr. asks this reporter if she’s seen ‘Field of Dreams,’ the 1989 film starring Kevin Costner who transforms an empty cornfield in Iowa into a baseball diamond. (She has.)

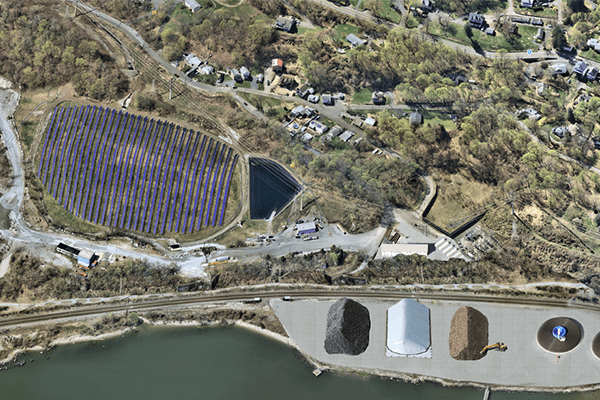

Haugland, the co-president of Haugland Group LLC of Melville, Long Island, mentions the film as a framework to talk about the company’s purchase of the former Mirant New York Lovett plant in Tomkins Cove, and how the shuttered power plant – a challenging contaminated site – can be reinvented to support the burgeoning clean energy offshore wind field and bring back jobs to Stony Point.

The Haugland Group under the name Tompkins CAMF, LLC of Melville, NY, purchased the 57-acre site from GenOn Lovett LLC in late 2020 for $2.85 million. Founded in 1999, Haugland Group LLC is an infrastructure services holding company whose subsidiaries and affiliates provide construction services for energy and civil infrastructure projects.

“This is an intriguing site,” said Haugland, adding it’s the first time the company has purchased a former power plant property. (The company owns a small power plant in Greenport, NY on land that it leases from the town.)

“The real motivator is around the off-shore wind industry,” he added, explaining that Haugland, a construction company that has a division specializing in the energy field, might use the site to store parts such as cable wire or “underwater mattresses” that are used to protect cable, and then ship the components on barges down the Hudson River to support projects in the growing off-shore wind farm industry that’s taking root off the Long Island coastline.

Haugland’s group of companies include Affiliate Grace Industries, which provides heavy highway, bridge, boardwalk, airport construction, earthwork, drainage, design/build, and other civil services. Haugland Energy provides turnkey construction, electrical power generation, transmission, distribution, and substations.

Haugland Energy is looking closely at the renewable energy sector including solar, wind, and battery fuel cell.

There are other possible but related uses for the former Lovett site, which the company has yet to determine, but its plans and the speed with which it gets up and operating may hinge on the expected passage Tuesday night at the Town of Stony Point town board meeting of a proposed a local law that would add a “floating zone,” to its planning toolbox for brownfield sites that specifically lie between rail and water.

The proposed legislation known as the “River & Rail Brownfield Redevelopment Floating Zone” (RRBR), if adopted, would be an amendment to the town zoning code.

“A floating zone is a zoning tool whereby you designate a zoning district, but you don’t map it,” said Max Stach, Stony Point’s Town Planner. “The law is designed to allow options for redevelopment of former industrial sites with river and rail access.”

The proposed law for floating zones evolved from discussions between the town and the former Lovett plant owners, which allowed New York State Department of Transportation to use its long-vacant property as a staging area or “logistics yard” during the building of the Mario Cuomo Jr. Bridge, and subsequently as a hub for the distribution of road salt.

Although the site has long been used for industrial purposes, it is zoned “Planned Waterfront,” which permits a range of uses including marinas, housing, mixed use, fuel and oil storage, restaurants, waterfront recreation and more. For Lovett, and other industrial sites along Stony Point’s Hudson River shoreline, a floating zone would allow the kinds of uses Haugland’s contemplating and would streamline zoning approvals if Haugland largely uses the site for logistics, staging, and storage rather than building facilities for manufacturing.

Haugland says the company is still contemplating the best use for the site, though it seems clear it will be used to support the energy sector in some fashion. There is potential talk of using the site for battery storage, solar panels, plugging into the onsite O&R substation. Possibly even stimulating its Tilcon quarry neighbor to fire up its operations once again to produce stone materials needed for the wind farm rock. “These projects will need more that 1,000 tons of scour rock, which is used in wind farm projects to protect against erosion,” said Haugland. “If we could get Tilcon to turn the quarry back on, that’d be a win-win. They mine the rock. We’d use our dock and the deep-water channel to ship the material to Long Island.”

Haugland is playing a role in an offshore wind project known as South Fork Wind that broke ground in East Hampton in February – New York’s first of its kind. The location will be the site of the junction for the export cable landfall for energy from 12 planned offshore wind turbines. Haugland Energy has been contracted by the project’s joint venture partners Eversource and Ørsted to install the underground duct bank system for South Fork Wind’s onshore transmission line and to lead the construction of the project’s onshore interconnection facility.

“The harsh impacts and costly realities of climate change are all too familiar on Long Island, but today as we break ground on New York’s first offshore wind project we are delivering on the promise of a cleaner, greener path forward that will benefit generations to come,” New York Governor Kathy Hochul said of the $2 billion project during a press conference last year.

The project will power approximately 70,000 New York homes annually; operations are expected to begin in late 2023.

The Lovett coal-fired plant in Tomkins Cove shuttered around 2007 after the state forced it to close because it failed to reduce emissions with new technology. Emissions from the 350-megawatt Lovett plant were linked to acid rain and smog. North Rockland residents were hit hard from a settlement that included paying the company $275 million to compensate for tax overcharges that dated back a decade. The effects of the plant closure, along with other shuttered industries, continues to be felt in the town.

Stony Point officials are focused on revving up its local economy, focusing both on reviving industrial properties, as well as residential and mixed-used development.

“We don’t want to see sites like this sitting idle,” said Stony Point Supervisor Jim Monaghan. “Haugland is anticipating a lot of growth in the wind farm industry. They’re looking at this site as a good location for this. We agree with them.”

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Haugland Group; Rendering Of Lovett Site