|

RCBJ-Audible (Listen For Free)

|

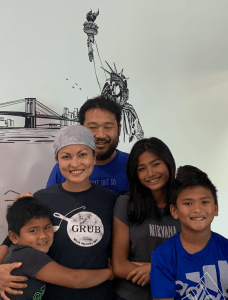

Waree Dinsay Has Turned Former Chase Building Into Asian-Fusion Cafe; Wants To Eventually Franchise Format

By Tina Traster

She had no plans on becoming a restaurateur. Through her childhood, she watched and admired her mother, who ran a restaurant in Southern Thailand, but she charted a path in the corporate world after earning an accounting degree from the University of Prince Edward Island in 2001.

Three years later, at 26, Waree Dinsay, married to a man from Rockland County, and living in Bangkok, listened to the true beating of her heart. She quit her job and enrolled in a two-year culinary course though the Oriental Hotel Apprenticeship program.

“My husband was so shocked,” said Dinsay. “He works in corporate. I was in corporate, wearing business suits. A safe path, with benefits and vacations. He was not expecting this even though I always cooked for him, and he knew I loved to cook.”

Fifteen years later, and during the height of the pandemic, Dinsay opened Grub in Village Square, 719 West Nyack Road in West Nyack in a former Chase Bank. The Asian-fusion restaurant is the pinnacle of a long journey that included a short stint learning her way around a commercial kitchen at PF Chang’s in Nanuet, leasing kitchen space at Parkside Tavern in Pearl River to sell her fare, and running two side-by-side eateries in West Nyack. She also returned to the corporate world temporarily when she and her husband Jeb, an engineer, first came back to the U.S. to start a family in Nanuet. The couple have three school-age children.

Fifteen years later, and during the height of the pandemic, Dinsay opened Grub in Village Square, 719 West Nyack Road in West Nyack in a former Chase Bank. The Asian-fusion restaurant is the pinnacle of a long journey that included a short stint learning her way around a commercial kitchen at PF Chang’s in Nanuet, leasing kitchen space at Parkside Tavern in Pearl River to sell her fare, and running two side-by-side eateries in West Nyack. She also returned to the corporate world temporarily when she and her husband Jeb, an engineer, first came back to the U.S. to start a family in Nanuet. The couple have three school-age children.

“I grew up around food,” said Waree, “I’d always make suggestions to my mom, like adding a complement to a dish. Or thinking up new dishes. But my mom didn’t want me to be in the food industry. She always said it’s a lot of work. A lot of headaches.”

Others, too tried to discourage Waree but she found the corporate world unfulfilling and could not resist the siren call of the kitchen.

“You know how it is,” she said. “You write up a report every week and the boss sees it and then it goes in the trash. There’s so much red tape. There’s the 3 percent raise. It’s safe and easy and it has nice perks but that’s nothing compared to the expression on a customer’s face when they bite into something you’ve cooked, and you see that face that says “mmmm.”

From 2009 to 2014, Waree was a stay-at-home-mom with an overwhelming itch to get into the kitchen. In 2015, after a quick part-time gig at PF Chang’s, she rented a kitchen in a biker bar for $500 a month. It was an experiment that gave the chef the signal she needed. She cooked burgers, wings and tacos at the bar. For two years, she fed bikers, built a customer base, cultivated online followers, and prepared herself for the next leap.

She began by renting a long-empty space in West Nyack for $2,000 a month, opening Grub Asian Fusion Cuisine. The venture paid off immediately, and in 2018, she expanded into a next-door takeaway location for burgers called Crossroads. For the first time, Waree may have bitten off a bit more than she could chew, having to run two kitchens and two separate staffs.

Not one to let moss grow under her feet, Waree took action. In late December 2020, before the world turned upside down and restaurants were called upon to adapt, the restaurateur eyed an empty bank in the vicinity of her eateries.

“I wanted to close the two places and consolidate,” she said. “It didn’t make sense to pay two rents, insurances. And parking was a factor.”

Retail banking is another industry in flux, even more so as a result of the pandemic. Many retail banks have been converted, particularly for restaurants because often banks are unique spaces with high ceilings, lots of light, and open plans.

However, choosing a former bank meant that Waree had to build a kitchen, install electrical and gas lines, and demolish the drive-thru windows – a more than $200,000 commitment that required taking a loan, snaking through approvals’ processes, and having the patience to turn a bank into a pleasing, COVID-friendly space. The bank agreed to remove the vault, which is something some secondary users of bank buildings repurpose creatively or simply lose the real estate space.

“The visibility of the building has great exposure,” said Waree. “People love the large windows and now parking is not an issue.” The 38-seat eatery with outdoor dining offers an eclectic spread of burgers, Indonesian fried rice, curries, and pad Thai.

Despite the pandemic, and nearly a year-long renovation while Waree kept the other restaurants operating, revenues in 2020 spiked. “We typically saw revenue increases of 20 percent year-over-year, but in 2020, we had a 30 percent increase.”

But Waree’s mother was right. Her daughter works 14 hours a day. She has navigated a complicated buildout of a restaurant in a bank building, she has made sacrifices to chase her dream.

And it will surprise no one – not her parents or husband or her customers – to learn Waree’s next desire is to franchise her concept. What she’s learned along the way is to be a visionary, to be flexible, agile, and adaptable.

“So many people lose their shirt,” she said, referring to the food business. “You have to be humble, adaptable, and to have empathy for how you’re impacting other people. In the end, you need focus.”