|

RCBJ-Audible (Listen For Free)

|

Assaults On Last Remaining Beach Road Residence, As Grassy Point Warehouse & Rockland Green Animal Shelter Destroy What’s Left Of Quiet Enjoyment Of Welsh Family Homestead

By Tina Traster

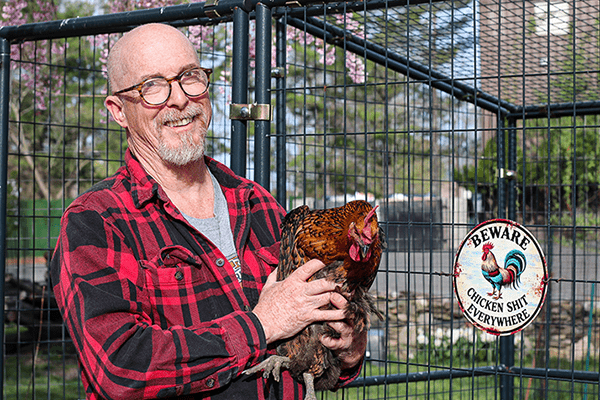

Paul Welsh is tilling his vegetable garden where he will grow tomatoes, garlic, asparagus, potatoes, and hot peppers he gives away to friends.

“I’m Italian,” he said. “I make sauce.”

Close by, four chickens are blissfully murmuring on a perfect spring evening, pecking at feed. All around, bright daffodils and exotic tulips show off their explosive riot of colors in lovingly tended flower beds.

This is Welsh’s pastoral oasis of beauty – a slice of Rockland that has survived, despite industry and insult, for decades. And it’s about to get much worse. Welsh’s split-level brick house at 423 Beach Road, built in 1962 on a third of an acre, has witnessed brick pits turn to fishing holes before becoming landfills on either side of his homestead. Large swaths of giant weeping willows were sacrificed when the Joint Regional Sewerage Board, which emits a constant sour odor, was built on Ecology Road. The Welshes lived across from a steel factory, which is a tile distribution center now, and surrounded by massive scrap yards – one right next door, the other also on Beach Road.

But now Welsh is beside himself with frustration as he endeavors to fight a 454,000 square-foot warehouse proposed on top of an uncapped construction landfill, and to protect a portion of land that he has stewarded for decades from the animal shelter that Rockland Green is building in a pre-existing warehouse – both on Ecology Road.

“On a Saturday and Sunday, this place is dead quiet,” said Welsh, 64, a sound engineer, eco-builder, and artist. “But it will never be again, and I hate it. I just want to retire and work on my art.”

Welsh has been attending contentious planning board/zoning board meetings in the Village of West Haverstraw, where residents living to the west of the proposed “Grassy Point Bend” warehouse, are worried about noise, lighting, 24-hour truck activity, truck traffic, flooding, and the potential impact of stirring up an uncapped construction and demolition debris landfill that was never properly closed but needs to be capped before anything can be built. The 34.1 acres of vacant land is bordered by East Railroad Avenue, Beach Road, and Ecology Road.

“I remember when that was a fishing hole,” said Welsh, referring to the late 1970s after the brick pits were retired, and before it became a dumping ground for construction fill. “If this turns into a 24/7 warehouse with constant truck traffic, it’s going to be horrible.”

Earlier this month, the Village of West Haverstraw Planning Board unanimously voted to accept a Final Draft Scoping Document for a Draft Environmental Impact Statement from the developers. The vacant acreage sits in the Village’s PLI (Planned Light Industrial) zone, which permits warehouse use as-of-right.

Welsh has another fight on his hands – one that affects just his homestead – the only remaining house on Beach Road in Haverstraw. The western strip of land his family has been using for decades does not belong to him. Rockland Green acquired the acreage when it bought the warehouse, along with two other structures.

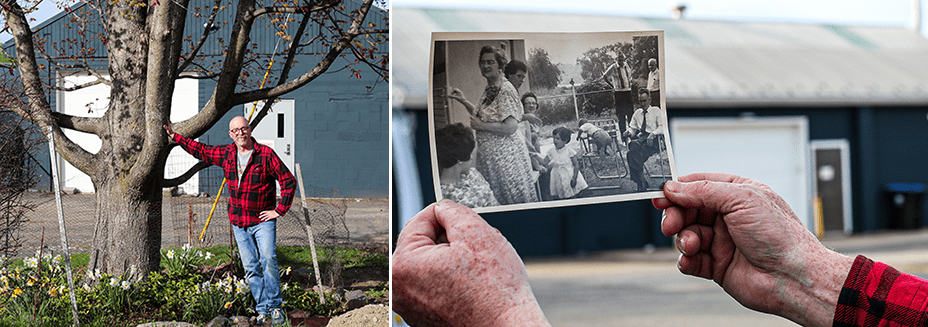

But a significant portion of Welsh’s hand-made wooden garden enclosure, along with flora and his favorite sugar maple tree are under threat because he may or may not have a legal claim to it.

In 2024, Rockland Green bought 3.4 acres from Beach Road Industrial LLC to convert an existing 15,000 square-foot warehouse into a $40 million (over 30 years of taxpayer bonding), 25,000 square-foot shelter that is underway after the tax-supported public authority tapped a North Carolina contractor last December.

Stony Point developer Bruce Smith built the warehouse on vacant wooded land in 2022. At that time, Welsh said he had a gentleman’s agreement with Smith, in which the landowners mutually agreed Welsh could keep his land and garden intact. Right after construction – long before Rockland Green commandeered animal management (snuffing out Hi Tor Animal Shelter of Pomona along the way), Haverstraw Town Supervisor Howard Phillips had his eye on Smith’s property. (Smith was involved in building the Joint Sewer Regional Authority, which Phillips heads up). The Town of Haverstraw in 2022 ordered an appraisal for the warehouse. In 2022, Smith had the warehouse up for sale for $4.2 million.

In 2022, after Rockland Green secured a change of its charter to include animal management, the vacant warehouse became a fast target for acquisition for Phillips’ future animal shelter. Rockland Green conducted less than a cursory search countywide for the place to locate the proposed shelter.

But Welsh figured the gentleman’s agreement he had with Smith would carry forward – after all, Welsh grew up in Haverstraw and remembers how things were always done. Francis Joseph and Lucy Welsh, who raised three children in the house on Beach Road, knew whom to call and how to get things done, back in the day.

“I remember one time the town broke a water main, which caused damage to the house,” recalled Welsh. “My mother got on the phone and ‘Tilli,’ (former Town Supervisor Phillip Rotella), who came down here with a bag of cash and said go ahead, fix it.”

It’s not possible to check the veracity of that memory but what Welsh meant was that there were unspoken pacts when people needed things to get done — promises were honored.

When Welsh, who lives with his disabled brother and his brother’s caretaker at the house, learned about Rockland Green’s purchase, he realized he’d lose some 25 remaining willows that he’d always thought of as part of his “backyard.”

“I met with Phillips and Damiani a few months ago and told them about the deal I had with Bruce,” said Welsh. But in early spring, the contractors showed up and began staking out the project. It became clear they planned to cut right through Welsh’s garden and other flora. The contractor’s plan to install three tall lighting posts along the rim of the property will destroy a 40-foot prized sugar maple, not to mention disrupt what’s left of Welsh’s rural slice of paradise.

Hoping to resolve the issue with another “gentleman’s agreement,” Welsh met with Jerry Damiani, Rockland Green’s Executive Director, and the contractor, who have indicated they will give the homeowner some leeway to protect what he’s built. Welsh says Rockland Green has agreed to build a privacy fence, but added he wants the agreement in writing because he’s not sure that the promises will be kept.

“These corporate people,” he mused. “I’m not sure they can be trusted.”

Back in November, Welsh said Phillips was trying to gauge whether Rockland Green could buy his house. Rockland Green had already purchased the warehouse, and two other buildings, for $3.8 million, and had paid Smith $225,000 for a year’s rent before the purchase was completed.

Welsh told Phillips straight out: the house is not for sale. The homeowner has lived in Vietnam, California and New York City but this oasis is his home now and forever. He calls it a “honeypot” because the taxes are low, and the land is his palette. Recently, he finished an auxiliary building on the property to house a very impressive man cave – which has a woodworking, metal, and sculpting workshop.

Welsh tells of colorful memories of growing up in the house. The Tappan Zee bridge steel was welded across the street at Kevin’s steel. The young Welsh witnessed strikes; one time the FBI came to the house, another time they heard gunfire.

“There were always characters, welders, junkyard dogs,” he said. “I remember Rusty. I’d ride my bike, and he’d chase me.”

He also recalls “we were surrounded by garbage and dust, and the Hudson was so polluted that you couldn’t swim in it. There was a constant oil sheen.”

The Welshes also put up with flooding from the Minisceongo Creek, which inundated the house with three feet of water during Hurricane Sandy (both Welsh’s house and the new animal shelter sit in a FEMA designated flood zone), underground fires from the landfills, and the building of the water treatment plan in the 1970s. Over time, other houses in the vicinity disappeared.

Ironically, Welsh, who is fighting to protect what he has inherited from his late parents, said “they couldn’t just move. They couldn’t sell the house. They had to bear it. The bad odors, nothing but trucks going up and down. And the junkyards, crushing cars. But my mom was tough as nails.”

Asked whether living in the house poses environmental concerns, Welsh said “my sister was sickly, my brother was born with Down Syndrome, and my mother’s sickness was tied to environmental issues.” But his father, who died in 2024, was 95 years old.

Welsh said he has no plans to uproot and leave the house, though a recent appraisal valued it over $500,000. “If I put it on the market in Brooklyn, every artist would want that. On Saturday and Sunday, it’s dead quiet.” Of course, all that’s about to change.