|

RCBJ-Audible (Listen For Free)

|

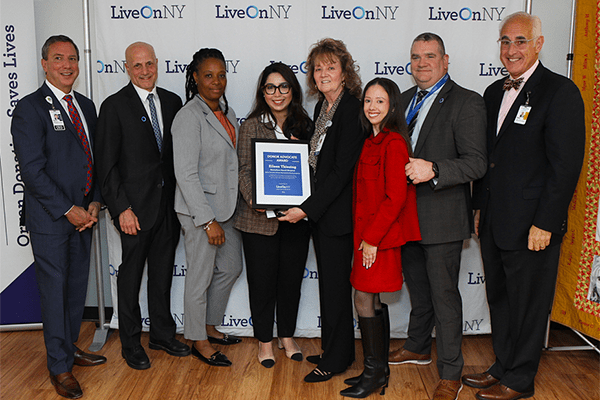

Lauren Shields, Hudson Valley’s LiveOnNY Community & Gov’t. Affairs Liaison, Uses Personal Story To Advocate and Educate

By Tina Traster

Lauren Shields grew up fast and with a purpose.

The double organ (heart & kidney) transplant recipient is literally the poster child for why organ donation is needed. Today, at 24, Shields serves as the Hudson Valley community and government affairs liaison for LiveOnNY, the federally designated organ procurement organization for the New York Metro region.

Last week, Shields spoke at an event at Montefiore Nyack Hospital to honor and thank healthcare heroes who support organ donation.

Healthy and full of vigor and passion, Shields uses a personal journey of hope and gratitude to bolster awareness of the importance of organ donation. At seven, an energetic bubbly child slowed to a crawl with fatigue. Doctors at New York Columbia Presbyterian Morgan Children’s Hospital in Westchester discovered her heart was operating at only 14 percent capacity.

“When they said I needed a heart transplant, I didn’t know what that meant,” said Shields. “I’d been in the hospital for days. I put my trust in the doctors. I realized that whatever they said needed to be done, needed to be done.”

The process was arduous, vacillating between hope and hardship, until a donor organ from a deceased four-year-old child in Illinois became available.

“I waited about a month and a half,” Shields said. “I was able to do arts and crafts. Students from Stony Point Elementary sent cards and chatted with me on video. But I got worse, I was sleeping more. Eventually I was placed in a coma for 15 days. My body was not doing well. I had tubes everywhere. I was growing weaker, but I never lost hope. I never assumed the worst.”

A few years after Shields received a new heart, former Sen. David Carlucci took office.

“New York had one of the lowest per capita organ donor registration rates nationwide, at just around twenty percent,” said Carlucci. “Today, over half of eligible New Yorkers are registered to become organ donors. This tremendous, life-changing achievement could not have been achieved without Lauren’s Law, a creative and personal approach to promoting the Organ Donor Registry.”

Lauren’s Law expanded the donor pool by requiring driver’s license applicants to say if they would be organ donors on DMV forms. Carlucci explains initially, the question would include a “no” option for applicants. “However, we found that providing a “no” option permanently opted an applicant out of the donor pool. Instead, we designed the questionnaire to provide a “yes” and a “skip” option, allowing for more chances to opt in at later instances and encouraging applicants to check “yes.”

There was no better way to tell New Yorkers why they should consider organ donation than to let the words flow from a recipient like Shields.

“We needed a compelling story to drive its passage to the Governor’s desk,” said Carlucci. “I was privileged to meet Lauren Shields and her family in early 2011. Instantly, I knew that the story about her life-saving heart transplant would be vital in enhancing the New York organ donor registration rates and, most importantly, saving thousands of lives in the state. Once Lauren and her family agreed to collaborate on this campaign, we decided to rename the bill Lauren’s Law. Lauren’s story transformed the policy debate from technical wording to the real-life implications of a simple choice. By humanizing the issue, we began removing the stigma around organ donation and set the New York State Organ Donor Registry on an upward trajectory.”

Following her heart transplant, Shields had a lot of work to do. Not long after her transplant, her parents divorced but her mother Jeanne was and remains her “rock.”

“My heart was working beautifully but the rest of me wasn’t,” she said. “I’d lost muscle mass, my hair. I needed physical and occupational therapy. Shortly after the transplant, I had a stroke.”

Shields is a fighter. She clawed her way back to health. She began her studies at Dominican University, initially with a focus on biology. But over time, she focused on health sciences and sociology.

“Sociology is the study of people and relationships,” she said. “How people help each other is of interest to me. I’ve been in a bad situation. People have always helped me, shown support, I truly believe in the good and kindness of people. I believe people are born to do good. And that life experiences can alter their path. That’s what happened to me.”

Twelve years after her heart transplant, Shields was suffering from kidney failure, likely due to anti-rejection heart organ medications, she said. This time the wait was pandemic related (it was 2020) but the donor was someone she knew: Mom.

“My mom saw how sick I was,” said Shields. “If she could have given me her heart, she would have. But now the time had come, and she could save my life with a kidney.”

Shields has never met the family who donated the young boy’s heart. Her mother had written the family a letter, and delivery of the letter was confirmed, but the family chose to remain private. “I’d love for them to see what their decision led to,” she said. “I’d love them to see how well I’m doing, because of their son.”

Shields recovered quickly and completed her degree at Dominican in 2022.

For many years, she’d volunteered at LiveOn, advocating about the importance of organ donations. Shields understands there is an intrinsic mistrust toward health care when it comes to organ donation. The organization works to educate and improve the understanding of the many and varied cultural belief systems and perceptions.

But every community and culture is capable of understanding the impact each individual can have on their family, their neighbors, their friends, their communities, through organ donation, she explained.

Shields has been shaped by her circumstances. She turned hardship into advocacy.

“Who I am today is because of what I went through at such a young age,” she said. “Every day I wake up and put my feet on the floor and I’m grateful because there were many days that were taken from me, many days when I couldn’t stand on my own.”