|

RCBJ-Audible (Listen For Free)

|

New Zoning Law Requires Farmers To Be On State/County Road, Have At Least Seven Acres, And Farm 51 Percent of Land To Qualify For Agritourism Activities

By Tina Traster

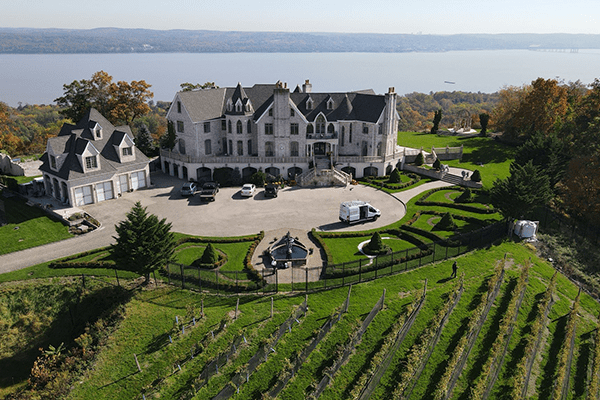

Joanne Clemente, a Town of Clarkstown resident who lives on 12 acres off Old Stone Road in Valley Cottage, has been growing non-organic grapes for five years. RiverWind Vineyard LLC had its first harvest last year. The vineyard raises funds for underprivileged populations but also showcases how it’s possible to farm and grow produce in a once-rural but increasingly developed community.

Clemente on Tuesday spoke out against Clarkstown’s intent to limit agritourism to residential properties that meet newly defined criteria: the site must be seven acres, situated on a state or county road, and 51 percent of the land must be used for agriculture.

“Everyone wants farms,” Van Houten said. “But a farm can’t exist without agritourism. This (Clarkstown) law is too restrictive. It needs more review and consideration.”

“The rules are too limited and don’t make sense,” said Clemente, on Wednesday. “They’re trying to quantify something that’s not quantifiable. It’s an experience.”

Clemente planted 700 red and white grape vines five years ago and reaped her first harvest last year. RiverWind Vineyard will eventually make its own wine. But its true purpose has been to raise money for disadvantaged communities: the proceeds of twice-annual fundraisers have been used to help build a school in Uganda. RiverWind is now partnering with Spring Valley-based NextGen, which is helping to raise funds for underserved students in the East Ramapo School District.

Over the years, Clemente has envisioned using the vineyard for agritourism – a priority for Rockland County, which consistently says tourism is a key aspect of the county’s economy. She says people will want to come and spend time atop West Hook Mountain to enjoy the vineyards, the Hudson River view, the patio and grounds.

But Clarkstown’s amended code, which was adopted unanimously on Tuesday, throws at least two obstacles in Clemente’s path. RiverWind’s vineyards cover two or her 12 acres, so she doesn’t meet the 51 percent threshold the law requires. Also, Old Stone Road is a private road: agritourism is only permitted on a state or county road.

Clemente, along with a handful of hopeful farmers and others, spoke out against the proposed amendment, which the town says is “intended to support and add economic flexibility to agricultural operations, and to promote new commercial operations.”

The amended law, originally proposed in April, began with restricting agritourism to 10-acre sites but was reduced to seven acres after some outcry that the law would be too limiting. The law also reduced the buffer around agritourism activities like food trucks and entertaining from 300 feet to 200 feet. And it reduced the requirement of having 300 feet of frontage on a state or county road to 100 feet. The Town Planning Board came up with the 51 percent restriction.

The Notice of Public Hearing published on June 10th, represented that 10 acres or more would be required to participate in the Town’s Agri-Tourism zoning, but when the public hearing commenced and the law was presented with a seven acre minimum requirement. A second hearing be required because of the lack of proper notice issued by the Town Clerk.

Farmers or growers who add agritourism to their operations will need a special permit from the Town’s Planning Board. But an agricultural operation with fewer than seven acres, or one that is not on a state or county road, will need to apply for an area variance from the Town’s Zoning Board of Appeals – which is often a nearly impossible hurdle to score in Clarkstown.

The law appears to boost agritourism in a town that is increasingly bearing the brunt of development and loss of open space. A closer look reveals that there are few undeveloped sites that would fit the criteria. The main exception is The Red Barn Cidery at Davies Farm — the only cidery in the town.

New City resident Marvin Baum, who has been reviving High Tor Vineyards on a three-acre parcel he’s recently bought off Little Tor Road, urged the town council to table the law for further consultation and research – and at least until a new ward member is assigned in his ward (the seat was held by the late Mark Woods, who died unexpectedly in May.)

“This law will hasten the demise of farms,” he said, also pointing out the restrictions were too confining, and that the law would preclude farmers from monetizing their operations through agritourism.

Town Planner Joe Simoes said the intent of the law was to create consistency in the zoning code.

“I want to make it very clear that agriculture is allowed in the town; we’re not changing that section of the code. It’s allowed in single-family zones.” He explained residents can have greenhouses, grow mushrooms, orchards, keep bees, he said. They can sell their agricultural products if they meet other requirement imposed by the town.

What motivated the town to define who and what kind of “agritourism” is allowed is the three-year saga in the Town of Orangetown that pit the Van Houten Farm’s Rockland Cider Works against neighbors who were angry at the noise, music, traffic, lighting and lewd behavior that resulted in the early days when the cidery opened during the pandemic in 2020.

The law, Simoes said, is aimed at “allowing agritourism uses while not causing undue nuisances,” he said. Citing Orangetown, he pointed out that food trucks, music, can be a disturbance to neighbors.

Simoes said farmers are entitled to hold “private events” on their property, but it leaves gray areas as to what is permitted and what isn’t, how often private events can be held, or just exactly how a private event is defined.

The United State Department of Agriculture defines a farm as “any place from which $1,000 or more of agricultural products were produced and sold during a calendar year.” New York State does not define a farm based on acreage, though equine and timber operations require at least seven acres. Clarkstown’s Town Code defines a farm as “any parcel of land containing at least 10 acres which is used for gain in the raising of agricultural products, livestock, poultry and dairy products.” Nothing in the town code is specific to wineries or cideries.

The Cropsey Farm, operated by the Rockland Farm Alliance, on Little Tor Road in New City is Clarkstown’s signature example of agritourism: the town/county owned farm is used for farm dinners, fairs, a CSA (Community Supported Agriculture), and education. Clarkstown also owns the former Traphagen Farm on Germonds Road but there is little farming or agritourism happening on site. Municipally-owned properties do not need special permits.

Protecting farming and promoting tourism is a challenge in a county that is increasingly becoming a bedroom community with a priority on single-family homes. Though public officials cite agritourism as an asset, the reality often competes with the desires of homeowners and residential neighborhoods.

However, farmers like Darin Van Houten, who recently shelved plans to resurrect agritourism for Rockland Cider Works after a three-year court battle with Orangetown and neighbors, told Clarkstown officials small farms cannot survive without agritourism.

“Everyone wants farms,” he said. “But a farm can’t exist without agritourism. Nowhere in the Northeast can farms exist without agritourism. This (Clarkstown) law is too restrictive. It needs more review and consideration.”

In the end, as it usually does when a proposed law is up for consideration, the fate of the bill was a foregone conclusion: the town council voted unanimously to adopt it.

“We are fine with moving forward on this law,” said Town Supervisor George Hoehmann.